Life is harsh on the rez. Residents are imprisoned in a strange duality where the natural world is both beautiful and holy. You are husked with an eternal expanse of robin’s egg blue sky silked with cloudstrands and a clarifying coldness. Yet the human sphere is filled with drug-fueled carnage. Hope does not dwell here. It is unfamiliar. Anxiety is constant, feeding core wounds. Pain is rote. Hunger, baseline.

Darvette Lefthand is a passionate community activist on the Stoney Nakoda First Nation Reservation. She has seen the carnage by methamphetamine wrought on her family and community. Darvette writes:

What can I do to feed my family?

To clothe them?

Shelter them?

Who am I?

Darvette Lefthand is a passionate community activist on the Stoney Nakoda First Nation Reservation. She has seen the carnage by methamphetamine wrought on her family and community. Darvette writes:

“It has been sad and heartbreaking on many levels. I’ve witnessed this drug take the lives of my community members, I’ve witnessed burials and the heartache that it leaves behind. I’ve seen the most greatest and brightest people lose their light to this drug, I’ve witnessed hard-working mothers and fathers that gave in and give up on the children, sons and daughters who lost themselves to the fight and to only have their own mothers and fathers, grandparents and family who cry and can only pray for them.”

When jobs are not plentiful, there seems little else to do, but experiment with something initially presented as relatively harmless. A brief kick. Darvette has seen countless times when friends cook and inhale the meth, or grind the powder then snort it.

The initial high exhilarates: it is an intense rush of pleasure and superhuman focus. Invincibility. You can hear your blood gush through your temples. The heart races like a cicada, and the comedown leaves a desiccated shell where the rush of life is spent, and the brain craves the next hit.

Methamphetamine has wrought devastation to Indian Country. Cartels have honed into the territory of Indian reservations for specific reasons.

The first is that the fuzzy legality and permeable boundaries allow for the perfect atmosphere for the shipment and distribution of illicit narcotics and tribal police are under-resourced and overstrained on any given day.

Then there’s the issue of interrelations between sovereign tribal governments and the United States and Canada. Drug cartels exploit understaffed reservation law enforcement entities and boundary disputes to optimal effect.

The second reason that cartels target Indian Country is that centuries of murder, rape, manipulation, land theft, and dehumanization have left the Indigenous populace so despondent that alcohol and drugs are ways of alleviating intergenerational trauma, especially when economic hardship and the unavailability of life-sustaining resources are endemic to reservation existence.

An analysis of census and survey data demonstrates conclusively that out of all ethnic groups of the United States, Native Americans experience the highest use of meth.

The statistics are horrifying. A study called Methamphetamine in Indian Country by The National Congress of American Indians states that in reservation and rural Native communities, meth abuse rates are as high as 30%, and growing. 74% of Tribal police forces rank meth as the greatest drug threat. The study declares that on reservations, 40% of violent crimes are attributed to meth. Violent crime in Indian Country in general also has a 40–50% rate of being attributed to meth.

Neuroimaging scans of people with a methamphetamine dependence show substantially altered neurology. The brain’s motor processing speed is reduced and verbal learning is impaired. Emotion, cognition and memory are all severely damaged with chronic users. Particularly affected are the body’s microglial networks, the guard cells of the Central Nervous System, which defend the brain against “infectious agents,” causing them to attack healthy neurons in a pattern of accelerated neurotoxicity.

“Delusional parasitosis” refers to a symptom that affects long-term methamphetamine abusers, where they are convinced that insects are crawling all over their skin because of a tactile hallucination known as “formication” thought to occur because of an excess of dopamine. Sufferers of these phantom insects scratch their skin unrelentingly and to no avail, resulting in cuts and sores.

Emotional lability, or severe and unpredictable mood swings, is a common denominator of long-term meth users. So is paranoia, and increased aggression and virility with decreased perception of and consideration towards personal boundaries. It is the perfect neurochemical recipe for physical, verbal, and sexual abuse.

According to a Treatment Improvement Protocol report by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSA):

American Indian and Alaska Native women report higher rates of victimization than women from any other racial or ethnic group in the United States. American Indian and Alaska Native women are nearly twice as likely to be raped or sexually assaulted than are white or African American women. Nearly 80 percent of sexual assaults against Native American women are committed by non-native men (see Amnesty International, 2007; Bachman, Zaykowski, Kallmyer, Poteyeva, & Lanier, 2008; Tjaden & Thoennes, 2006).

People living on the reservation are left stranded. The lack of job opportunities creates a vacuum in place of an atmosphere; no one is able to breathe and thrive. Darvette writes,

“Some reservations have a solid healing foundation which includes the support of their Chief and Council system and the community members, who come together to create an idea and get facilities up and running which create programs and a plan to get people into sobriety. And others along with my reservation don’t have any other support or facilities, nor encouragement from the chief and council system.”

Darvette continues:

“Many difficulties are presented when living on reservations. This can range from lack of jobs and training, to resources like outreach programs, food banks, and funding for proper training and education.”

“Living on reservation can mean you find yourself far from the main cities and towns having to travel far to get the basic necessities. Like groceries to last you the night, week or month, or things your children or yourself need. Some individuals have troubles with transportation and need to ask around for rides. Some take cabs or simply walk when they can’t find any means of transportation. Many people of various ages and gender status need basic services, but can hardly access them.”

Long term studies monitoring recidivist rates indicate where there are healthcare services, they infrequently center Indigenous peoples’ specific worldviews and traditions. Western orientation of medical care can be re-traumatizing, reinforcing colonial patterns that brought them and their ancestors to a state of devastation.

Darvette writes,

“Colonialism has always affected our Indigenous lives. In many harsh ways it played a big part in our history from first contact well on into today’s world. It has affected many tribes, nations, clans in many different ways which caused many different difficulties for the past and present. It has traumatized us in such ways as taking the lives of innocent individuals: children, women, men, even elders were murdered and assimilated all in the name of “new land” & “colonialism” it has traumatized us by taking our traditional ways of life.

To us, our cultural aspects and indigenous voices are as one, whether as individuals or taken as a collective. And it has been what started the assimilation of Indigenous peoples all throughout the United States and Canada, as well down in South America.”

The concept of retraditionalism has garnered more support in the past two decades. The concept reintegrates Indigenous cultures with the full suite of resources of their ancestral past, in effect re-forging a lost link.

The Welbriety Movement was founded in 1994 by Don Coyhis, a Mohican tribal member born and raised on the Stockbridge-Munsee Reservation in Wisconsin, with the intention of interweaving Native American principles and ethics into recovery programmatics. The Wellbriety Movement program comprises differently-lensed insights than those commonly found in 12-step standalone structures. It sees recovery and the concept of wellness holistically. Yes, alcoholism is a disease. But the disease is wider than its host organism. It is the entirety of the ecosystem, this requires restoration and balance. Its precepts are The Four Laws of Change, which were received from an Elder in New Mexico in the mid-1980s. They state that:

1. Change is from within.

2. In order for development to occur it must be preceded by a vision.

3. A great learning must take place.

4. You must create a Healing Forest.

The essence of retraditionalism is about realignment and the restoration of balance. Darvette says,

“I do believe retraditionalism can help with recovery. The main reason for our peoples’ trauma is colonialism, and it’s the main reason for us as individuals and a community to lose our cultural ways and indigenous ways of life and our language. To lose ourselves as Indigenous peoples.

“Smudging can provide strength and courage, a talking circle can provide moral support and relearning traditional roles both genders played like the women learning to cut meat and beadwork can help a woman heal as some nations believe that working with your hands can help you heal, and gain wisdom. As for the men, learning to hunt, trap and fish as well as building can help a boy or man gain knowledge on how to feed and care for himself and a family. Many other traditional ways can definitely help our people win in the battle against drugs.”

The medicine wheel encircles existence. She has come to participate in Ceremony. Ceremony for the loved ones who have passed. Ceremony for the afflicted living needing protection, family, friend, foe, and stranger alike. She has come, too, for her own healing. She has come to speak with the Creator.

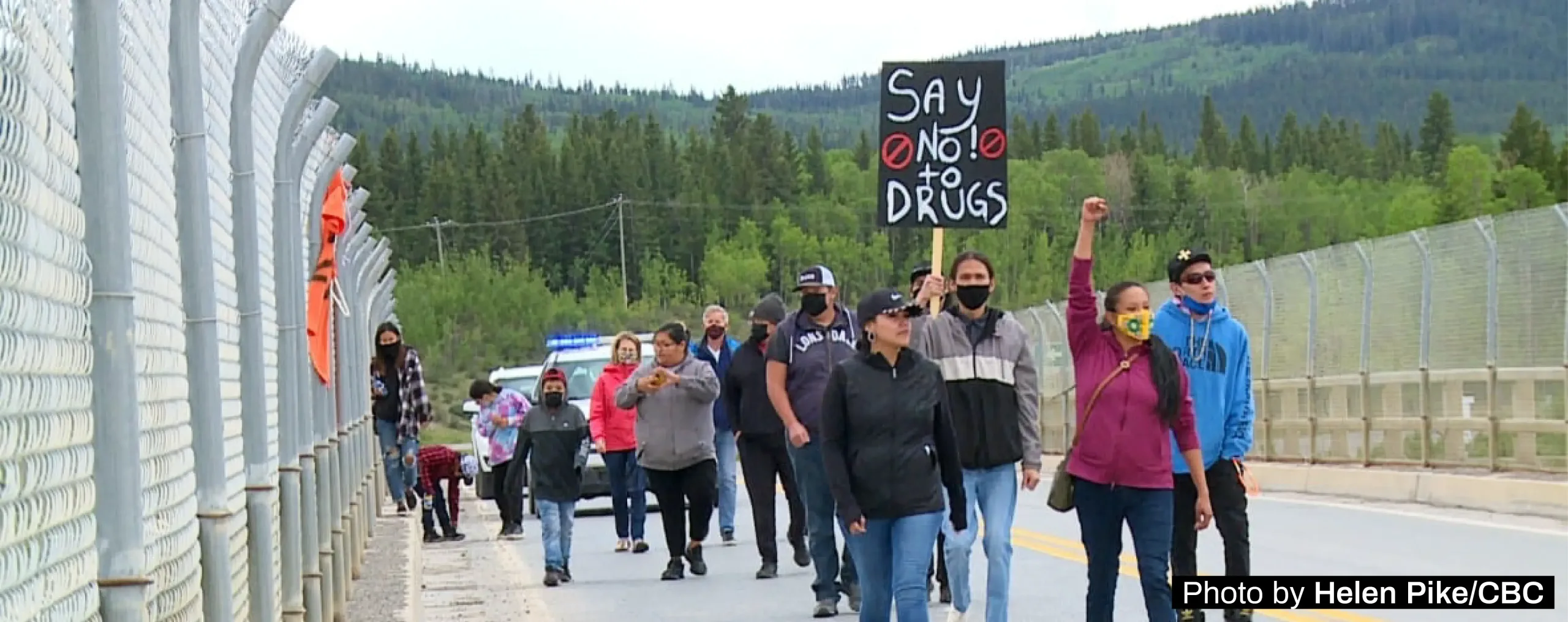

The group that has assembled in Stoney Nakoda Nation is called Wácágâ ôkóná’gîcíyâ’bî, which roughly translates to “A shield that provides protection both physically and spiritually.” Their official Facebook page states that:

“In the old days some warriors carried their medicine powers on their shields when going into battle, this ensured that they would return. In this present day, we are warriors entering into battle with this initiative to fight for our people. In the old ways the warrior shields were known to stop bullets, in today’s society those bullets could be anything from negativity, jealousy, or the darkness of politics.”

Awaken the sprout of regrowth in yourself, of new life, as a re-blossoming tree. Shed acorns, pinecones, for the foraging animals who know the cycles of life. The forest is holistic, regenerative. The soil smells rich of humus and peat. What once was ravished and barren of life restores its health and vitality, but not alone. Everything is interdependent. Connected. An interwebment of life. We all need one another. Growth is a fundamental aspect of the universe. It is not without pain and suffering, but this leads to breakthrough and joy and the restoration of balance. True strength is not about the ability to endure pain, but to use it and go inwards to find its source, realizing that we all need one another and none of us can do it alone.