The elements are permanent in our cultural psyche. We witness crowds waving and cheering pressed against metal stanchions, marching bands echoing the streets with a catchy tune to the lead of their grand marshal. Mylar-decked floats transport people we admire as they wave elegantly to the crowds. We consume in awe the breathtaking pageantry and sometimes our beloved characters as gigantic helium-filled balloons tethered by proud marchers. Its origins trace back to Middle French, meaning “to prepare.” We know them as parades.

It’s easy to take for granted; our immediate thoughts are all the elements that make it fun. At their root, parades are a collective statement given by a community, sending off into cultural consciousness a confirmation of their identity. While these events are always a reason to celebrate, our most electrifying parades stem from a fight for freedom.

We appreciate parades even more as many of our communities were happy to have them back after a two-year hiatus from the pandemic. In Portland, Oregon, Debra Porta, executive director of the nonprofit Pride Northwest, said, “The isolation is real for our community, so there’s nothing that beats the energy, the vibe, of being in-person,” Porta said. “Our strength in numbers reminds us that we’re not alone.”

Historically, in the United States, military parades have long been used to either boost morale or celebrate the end of a harrowing conflict. During the Revolutionary War, George Washington boosted military and patriotic morale with social gatherings and a pomp-and-circumstance procession, where he was often the focus. Even in the afterglow of victory against the British, he foresaw the possibility of patriotism reversing itself and becoming a protest, political divide, and eventually civil unrest. As the only president to avoid claiming a political party, Washington believed political factions and parties were antithetical to the goal of democracy.

Washington’s foresight has proven to be accurate. By the 20th century in The U.S., the demographic landscape radically changed through great migration waves in major cities like New York, San Francisco Bay, Chicago, and New Orleans. The American landscape and its cities began to transform with new communities of immigrants and Black Americans who had moved to cities and established communities in pursuit of the “American Dream.”

Ideally, the participation and integration into American culture would have been met with prosperity for all communities to share on an equal basis. However, our nation’s very-known history of inequity and subsequent civil unrest sparked action from communities to demand reform by way of protests. We’ve endured in our history fatal riots, fires, and police raids–all painstaking and horrific–which gave way to protests of lamentation and appeals for change. Much like the Greek Agora, public space was and is a lobby for equality and social freedom.

We trace the origins of Pride to June 28, 1970, one year after the police raid at the Stonewall Inn in New York City. The first Pride marches were held in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. Before we could parade with Progress Rainbow flags and all that glitters, thousands of LGBTQIA+ people gathered to demonstrate equal rights in commemoration of Stonewall and all places where inequality and violence took place. It has taken decades of activism and the rise of equality organizations to evolve into today’s joyous celebration. Pride traditions were adapted from the “Reminder Day Pickets” held annually (1965-1969) on July 4 at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

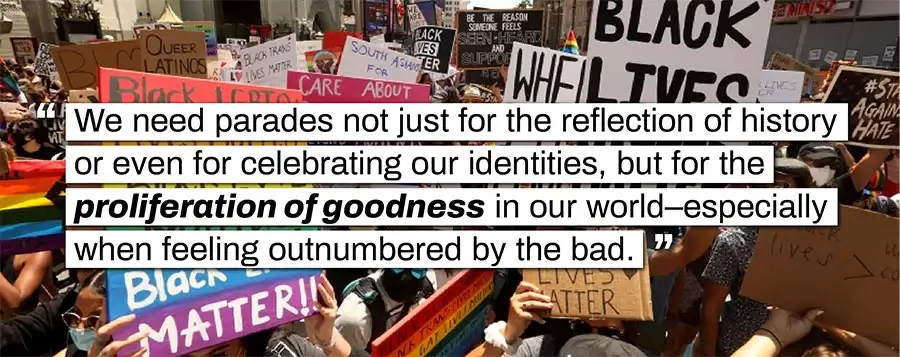

In our celebration of Black heritage, we look back beyond the Civil Rights Movement: from slavery in the South to emancipation that continues to only be partial in its liberation. While it’s taken centuries for Juneteenth to be recognized as a federal holiday (as of June 2021), much work lies ahead. The movement Black Lives Matter furthers this demand by continuing to march for more than just civil rights but the demand for justice for the many lives unnecessarily lost in recent years to police brutality, racism under the guise of vigilantism, and the continued civil unrest in an unjust system. While so much adversity is still at stake, a reminder to remain proud of one’s identity, heritage, and perseverance is paramount. It is this very humility held by thousands that evolves a protest into a joyous parade.

We need parades not just for the reflection of history or even for celebrating our identities, but for the proliferation of goodness in our world–especially when feeling outnumbered by the bad. In the movie Pay it Forward, the main character, Trevor, is given an assignment by his social studies teacher, Mr. Simonet, to find a way to change the world and put it into action. Trevor conjures up the Golden Rule: the notion of not paying a favor back but paying it forward. In other words, to repay good deeds not with payback but with new good deeds done to three new people. Do something good for someone then that person pays it forward three times as well.

We can see the Golden Rule implemented in our large festivals and parades. In Philadelphia, the Odunde Festival was created by former social worker Lois Fernandez. He received a $100 grant and started the first Odunde Festival. What began as a gathering of 50 people is now a fifteen-block celebration of identity and African roots.

When marching, cheering, and waving flags, we should ask: what grounds us and keep us proud of ourselves? How do we remind ourselves of progress? Maya Angelou said, “a solitary fantasy can totally transform one million realities,” meaning that any glimmer of hope and even a brief moment of fanfare can be the pavement for a better future. The Golden Rule is simple, almost childlike, but profound in its effect.